Punctuating Calamity

Eliot Weinberger and Ismail Ibrahim on “House Arab”

When Ismail Ibrahim set out to write about his experience as a fact-checker at an unnamed American magazine after October 7th, we suggested he look up Eliot Weinberger’s essay, “Where Was New York?” In his quietly devastating commentary on E. B. White’s “Here Is New York”—a beloved 1948 New Yorker article by the author of Charlotte’s Web and The Elements of Style—Weinberger skewered the self-sure provincialism of The New Yorker’s vision of New York. “For some eighty years the magazine has represented the Zeitgeist of the upwardly mobile educated white Manhattanite,” he wrote in 2002. “It is permanently fixed in an air of bemused detachment, which it expresses in a style whose sentences are pathologically rewritten by its editors, “polished” (as they call it) until every article, whether a report from Rwanda or a portrait of a professional dog-walker, sounds exactly alike.”

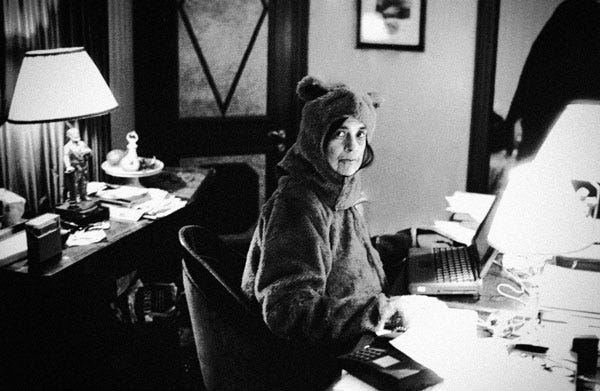

Weinberger is the legendary translator of Octavio Paz, Jorge Luis Borges, and Bei Dao, and the author of some 20 books on, well, whatever the fuck he finds worth writing about. He is also one of the great political essayists of our time, as evinced by his widely anthologized 2005 essay, “What I Heard About Iraq,” published in The London Review of Books during the locust years of George W. Bush.

Not coincidentally, Weinberger is one of Ibrahim’s literary idols. We brought them together to discuss “House Arab,” writing amidst disaster, and fact-checking as genre.

Eliot Weinberger: Hi Ismail… Many people go from fact-checker to editor at the New Yorker, but you are surely the first to go from fact-checker to Talk of the Town. “House Arab” may be Bidoun’s greatest hit. Any thoughts why? Obviously it goes beyond the liveliness of the writing.

Ismail Ibrahim: That’s a great question. I really believed “House Arab” would be a minor incident, only of interest to brown people working in media institutions who similarly felt at odds with their employers, though, as you mentioned, it sort of escaped containment… I think part of the spread is that the mea culpa I predict at the end of “House Arab” has begun. In July, the New York Times, a publication whose sympathies are no mystery, published an op-ed declaring the Gaza war to be a genocide, and, in Kamala Harris’s new book, she cynically writes that she privately disagreed with Biden’s position on Palestine. So, I think part of its appeal is that it names something the reader can see happening and that they are rightfully mistrustful of.

The other thing is that I would like to think that the piece works, in part, by de-emphasizing the importance of “reality” as a set of mutually agreed upon facts. The world “as it is” is as real to the narrator as the possibility of a more just world. To be a fact checker is, in many ways, to be totally obliterated by reality, a feeling I think many readers can “relate” to. (I have never understood reading to relate to something. I want to experience a consciousness profoundly unlike my own when I read. I get enough of myself just living). On top of the Gaza genocide, there are the mass shootings, the ICE raids, the Ukraine war, the rising cost of living, the climate crisis, and on and on and on and on. Reality feels like a brutal joke right now.

You say “obviously it goes beyond the liveliness of the writing,” and I agree, but it was important to me that the writing be bouncy, the tone ambivalent. I have been thinking a lot about the relationship between the New Yorker’s plain style—the voice’s inability to be genuinely surprised by something, its projection of both distance from, and total knowledge about, the subject under discussion—and the magazine’s acquiescence to status quo politics. In your essay on Susan Sontag, you discuss her contribution to the New Yorker‘s post 9/11 issue, the only one that pointed out that the attack was a consequence of US foreign policy. Despite its “bad manners,” what she writes, in hindsight, seems self-evidently true. The hostility she was met with—not to mention the genteel essays from Franzen et al. it appeared among—seems of a piece with the nativist politics we are living with now. ICE, of course, being a creation of Bush II.

EW: The issue that immediately followed 9/11 has always struck me as the quintessence of the New Yorker. Rather than allude to it, I’ll do something I have never done, which is quote myself, since it is an accumulation of telling details. It opened my Sontag review in NYRB, but Bob Silvers refused to print these paragraphs. (It’s now in one of my books.):

After the nearly all-black portrait of the Twin Towers by Art Spiegelman; after the ads for Ralph Lauren Polo, Mercedes-Benz, and Laurent-Perrier champagne; after eighteen pages of the usual “Goings On About Town” (“Chef Rick Laakonen spent his woodsy youth among Massachusetts Finns”), and before the longish articles on the Boston Red Sox, new productions of Verdi, and the latest cookbooks, a group of writers were asked to comment on the devastation that had just struck.

John Updike, who “happened to be visiting some kin” in Brooklyn, raised his well-worn descriptive binoculars (“it fell straight down like an elevator, with a tinkling shiver and a groan of concussion”) and ambled to a cheerful conclusion: “The next morning… The fresh sun shone on the eastward façades, a few boats tentatively moved in the river, the ruins were still sending out smoke, but New York looked glorious.”

Jonathan Franzen recalled a personal “recurring nightmare,” invoked “a childish disappointment over the disruption of your day, or a selfish worry about the impact on your finances,” and lamented the “loss of daily life”: “your date for drinks downtown on Wednesday,… the hourly AOL updates on J. Lo’s doings.” Roger Angell reminisced about World War II and “a lifetime of bad news: your neighbor’s son’s car crash, your tennis partner’s blastoma, Chernobyl, or the Copacabana fire.” Rebecca Mead, comparing the National Guard barriers at 14th Street to the “velvet rope at the night-club door,” rather happily noted that “exclusivity” had been “restored” to a lost bohemian downtown Manhattan. And then there was Susan Sontag, blasting in her first sentences through the cluelessness and The New Yorker style-must-go-on prose.

Now I don’t think this is “nativist,” in the current iteration, but utterly provincial, and of course unable to imagine the political beyond the personal. It’s so New Yorker to reduce everything to its little world: Chernobyl is like your neighbor’s son’s car crash. I’ll never forget their reporting on the genocide in Rwanda, where they found it necessary to explain that Rwanda is the same size as Connecticut.

II: There is an element of “provincialism” to it, but if you are so insulated, as a provincial is, you think your land is the only land that matters. That is a form of exceptionalism. Comparing your neighbor’s son’s car crash to Chernobyl betrays a consciousness that can be undisturbed, for example, by civillian drone strikes in Yemen. Does that make sense?

EW: I think there is a huge difference between New York provincialism and nativism as currently practiced by the Trumpistas. Nativism is the overt hostility to everything that is not local. Provincialism reduces everything to the local and sees everything through the local. New York provincialism is occurring in the most international city in the world, so obviously it has a greater range of the “local” than a small town in Alabama. New Yorker-type “intellectuals” are not xenophobic, but they are apparently unable to think about the larger political contexts of events such as 9/11 or 10/7. What they understand is victims, which is why they supported the invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq, until they turned against it, and supported Israel until the genocide in Gaza became evident to them.

But let’s get back to “House Arab.” What about the fact-checking obsession in American magazines? In the old days, it was limited to potential libel. The New Yorker notoriously expanded it to legions of the recently graduated checking (in your example) at what exact minute in the Almodóvar film Penelope Cruz has sex, and this has now become standard practice in magazine publication. The result is endless hair-splitting between writers, who presumably know something about their subject, and fact-checkers, who only know what Google tells them—and, of course, the writers are presumed guilty until they can prove their innocence. Most of it is deeply pointless. And your case, in its way, takes it to an extreme: You were forced to ask Palestinian villagers to recount incidents of horror, which would then be retold in the New Yorker style of the arched middle-brow, running in faint type between the unchanging cartoons of cave men, princesses in castles, and suburban living rooms.

II: Part of me wants to say that obsession is a recent innovation with “the information age,” that accuracy is taken to be a good in itself, and no hair is small enough to be split, though I recently re-read part of Tropic of Cancer. Miller’s narrator (or Miller himself, I was never clear on this point and don’t wish to Google it!) becomes a copy editor at a newspaper. “The world is brought under my nose and all that is requested of me is to punctuate the calamities” he writes. The newspapermen “live among the hard facts of life, reality, as it’s called.”

EW: Miller was indeed briefly a newspaper copy editor/proofreader. But punctuating the calamities is not at all the same as asking the victims of calamity to affirm (or prove) that they are victims. I just find that calling these villagers—and making you, as the “House Arab,” call them—is grotesque, and typical of the New Yorker’s insufferable self-regard.

II: In one way, yes. Punctuating calamities is different than running the victims of such calamities through the facts of it, making sure to specify that it was “sheep dung” they were forced to eat by their captors, rather than some other animal’s feces. What interests me about the Miller quote, though, is the posture toward the world’s calamities. That was what was being asked of me—to leave the events I was verifying under my nose, not to bring them to eye level while I prodded around to ensure they were “true.”

In the last year, since I left the job, I have paid close attention to my dreams and my imagination. I love films like Meshes of the Afternoon, Orphée, and Lost Highway, where the “hard facts of life” are violated to achieve a different kind of truth, a different kind of reality. The universe is not all that is the case, as Wittgenstein put it, though the universe of The New Yorker is. I think being a fact checker impoverished my ability to engage with “the other side.” I am trying to recover that sense.

Hot Tangents

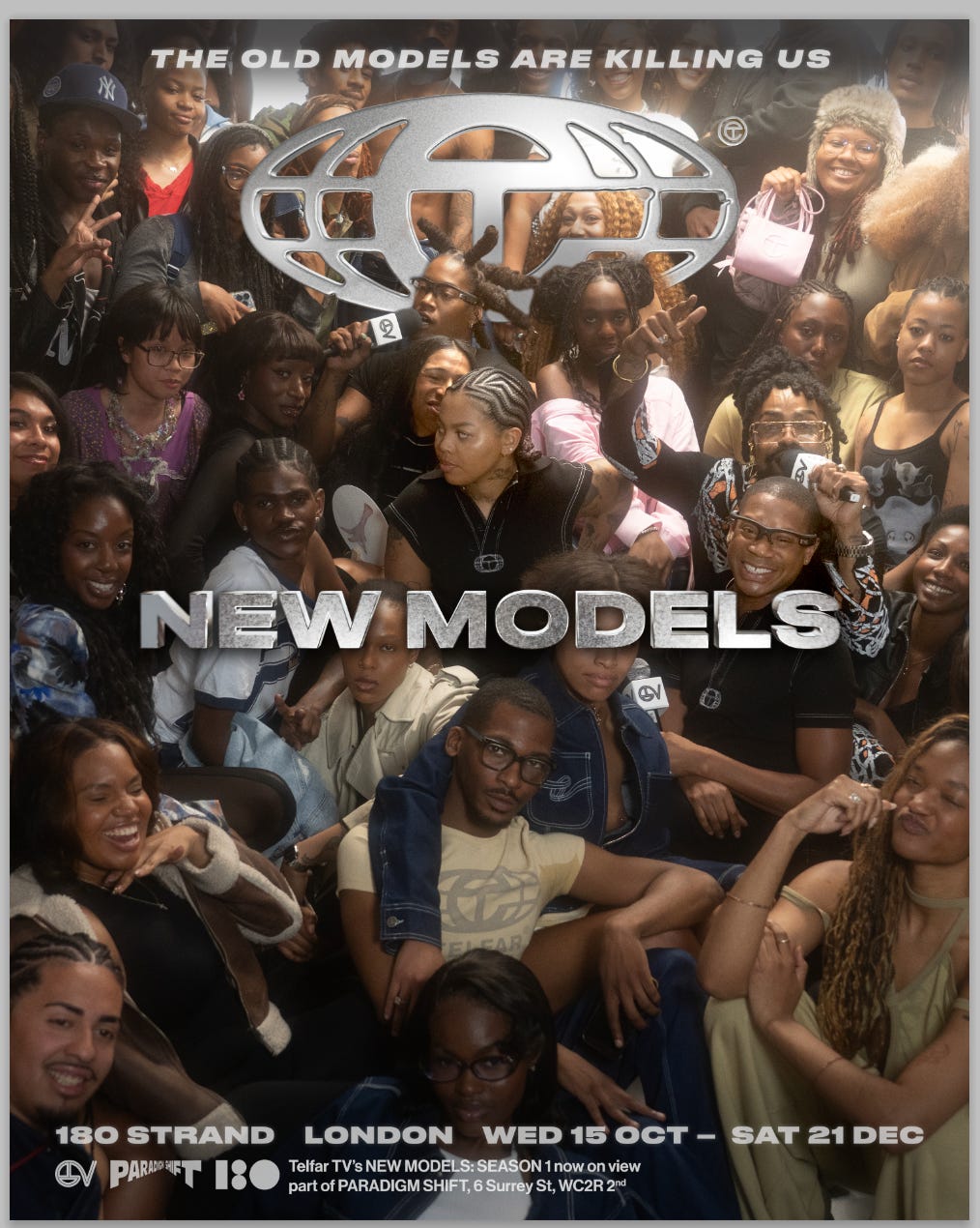

Bidoun’s longtime Creative Director Babak Radboy, who serves as Creative Director of the black-owned fashion brand Telfar, will be staging a live television show in London during Frieze week. New Models is TELFAR TV’s first series: an eccentric experimental reality show in which open castings are held for ‘New Models.’ Typical of the brand’s bonkers and irreverent anti-industry politics, candidates are put through challenges, while organizers suggest they were never referring to fashion models in the first place, but new models of social and political organization and resistance.

Ibraaz is open today, October 15th: a new space in the heart of central London dedicated to “art, culture, and ideas from the Global Majority,” reimagined by architect Sumayya Vally. An initiative of the Kamel Lazaar Foundation, Ibraaz launches with an exhibition by Ghanaian artist Ibrahim Mahama, a library-in-residence project by the Otolith Group, and loads of ambitious programming.

Les Chichas de la pensée, the itinerant discursive cultural project run by Mehdi Meklat, Badroudine Saïd Abdallah, and Asma Barchiche, is hosting a weekend of screenings, talks, and performances at Fauvette City Club, a new venue in the Parisian suburb of Saint-Denis. The event (October 24–25) commemorates the 20th anniversary of the deaths of Zyed Benna and Bouna Traoré—two young men whose passing set off countrywide anti-police riots in 2005. Filmmaker Alice Diop, choreographer Tchomanga, and the rapper Prototype are among thirty artists taking part.

Our friends at the invaluable Palfest have launched a new podcast on and around the Palestinian literary scene. The first episode features young Gaza-based writer Batool Abu Akleen. Another Palfest event to look out for in London later this month: a conversation on Palestine and Kashmir with Isabella Hammad and Mirza Waheed at the Southbank Centre.