How Excruciating Can Nothingness Be?

Revisiting Jack Kevorkian, Painter

Read A Very Still Life: Jack Kevorkian and the Muse of Genocide, by Anna Della Subin published in Bidoun, Issue 27 Diaspora on Bidoun.org.

On Reddit, there is a forum where beachcombers and scavengers convene, a tribe you might glimpse with headphones and metal detectors, listening for a pulse in the sand. The latter-day diviners of “r/TreasureHunting” tout their finds: old Boy Scout medallions and rusted spear tips, bullet casings from World War II, an aardvark coin from Zambia. A few months ago, fellow Bidouni Alex Keefe alerted me to a recent post. A Chilean man living in the port city of Valparaíso had purchased a villa that had belonged to a local eccentric, “an obsessive collector of everything imaginable.” The house was sold as-is, and it turned out to be packed with the dead man’s belongings: a lifetime’s worth of oddities, acquired at auctions. Among its mysteries were the contents of a shipping container that once belonged to the late Jack Kevorkian, the Armenian-American pathologist, polymath, and pioneering advocate of the right to kill yourself.

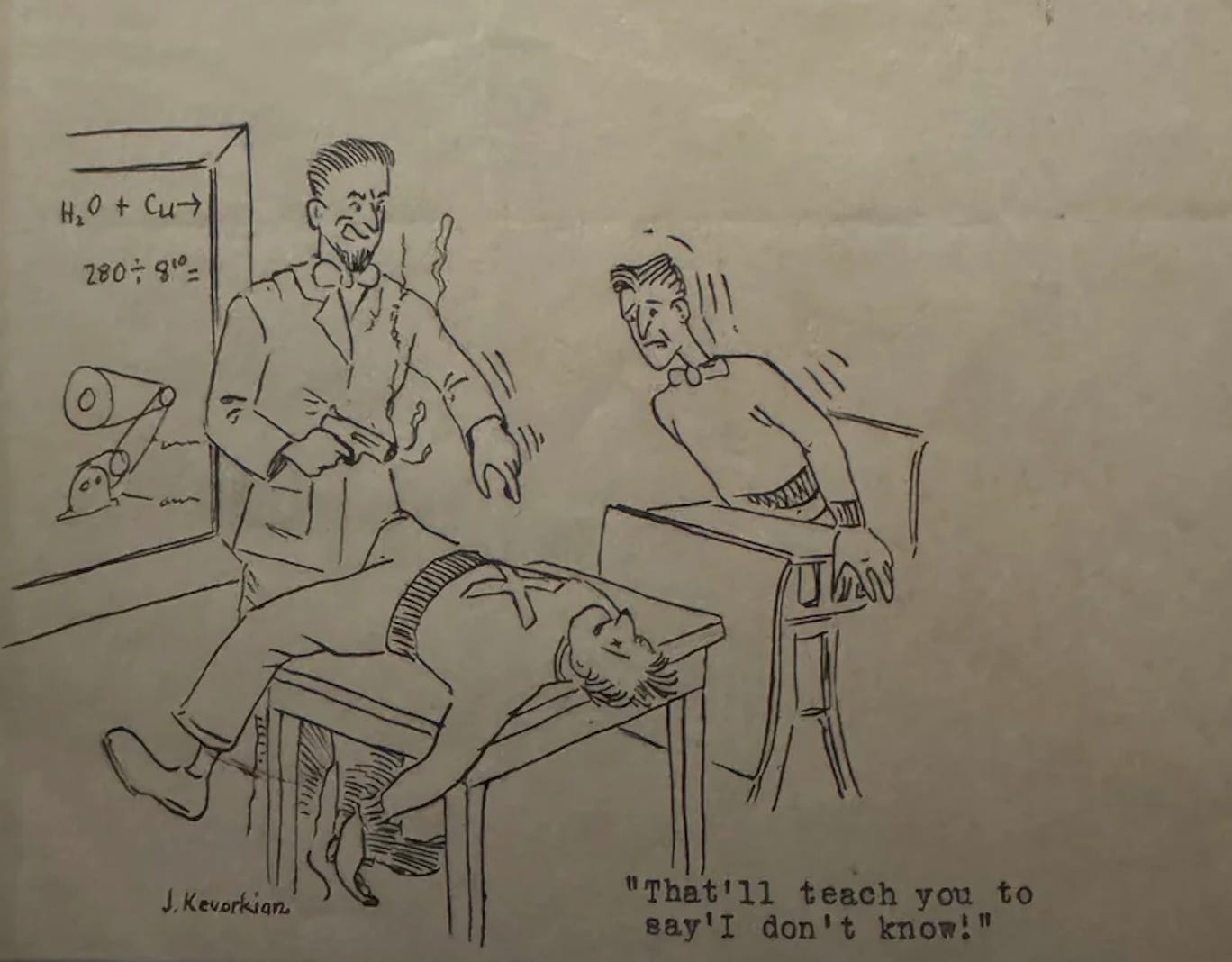

In 2012, I wrote an essay for Bidoun that reflected on how a child of the Armenian genocide became “Dr. Death,” the patron saint of euthanasia. It was prompted by an exhibition at the Armenian Library and Museum of America in Watertown, MA, of Kevorkian’s macabre paintings, usually well-hidden from public view. They are full of horrors: a man falls, screaming through a void, dragging his fingernails to the bone; another is feasting on himself. A greenish corpse ornamented with tinsel stands in agony, a human Christmas tree.

Kevorkian’s painterly eye was staring straight into hell. He was an autopsist, I wrote back then, from the Greek meaning literally “to see for oneself”—observing closely what happens at death, to people and peoples, both. Genocide haunted the premises; at the door of the museum, the receptionist handed me a chronological list, ending with a foreboding, “Who Is Next?”

Accompanying 1915 Genocide 1945, a painting of a severed head dripping with Kevorkian’s own blood, a plaque read: “To fail to take but token interest in the whole ugly affair, to avoid making it almost hereditary memory, would be abdicating decent human responsibility and thereby assuring recurrence is happening at this very moment.” Harrowed by an atrocity that pre-dated his birth, Kevorkian took on not its human perpetrators but Thanatos itself, driven by the conviction that all people should be able to die with self-determination, to slip off into the dreamless night with dignity and in peace.

By coincidence, I first visited the paintings at the ALMA museum the same weekend in February 2011 that Hosni Mubarak fell from power in Egypt. Soon, with the rest of the Bidoun team, I was on my way to Cairo; caught up in the afterglow of the uprisings, I set aside the darkness of Kevorkian. I wrote another essay for Bidoun about political figures unwittingly turned divine, which would become my book, Accidental Gods. By the time I returned to Dr. Death, I was well on my way to becoming an expert in apotheosis. Kevorkian became a sort of Bidounish god of the underworld—whimsical, charming, perverse. Revisiting his life and art in the shadow of the ongoing atrocities in Gaza reminds us of how genocides, even after the killing has ended, take on afterlives in ways we cannot predict.

Many of the sixteen paintings in the exhibition were Kevorkian’s own feverishly repainted copies of originals that were, I wrote, “lost by a moving company when Kevorkian moved to California in 1976” to direct a Hollywood film of Handel’s Messiah. The Reddit revelation offers a coda to that story, the Chilean trove being, effectively, the archive of Kevorkian’s life, from his birth in Michigan in 1928 to 1983. It includes his childhood report cards, school essays, and diplomas; sketches and comics; bank statements and cheques; journal entries composed in various shapes: a crucifix, a labyrinth, a soldier’s silhouette, and his initials, J K. There are photos of dead bodies, letters to art collectors, music scores, and the lost reels of his failed Messiah. It seems likely that, rather than being lost in transit, Kevorkian’s possessions were sold at auction when he fell behind on payments for his storage unit after going bankrupt making the film.

That the stuff of Kevorkian’s life should come to rest in Valparaíso makes a kind of historical sense: in the 1920s, Armenian survivors arrived in the nearby town of Llay-Llay seeking refuge. In 2015, the Chilean government officially recognized the genocide.

As for the paintings? The Valparaíso buyer, posting only as JJ, recounted that one night, he invited friends over for dinner:

One of my wife’s friends, who grew up in the same neighborhood as the collector’s family, froze when I said Kevorkian’s name. “Dr. Death?” she said. She then told us that when she was 14, a neighbor played a prank on her and her friends by leading them to the rooftop of his house, where they found a horrifying scene: 15–20 huge paintings depicting satanic imagery—blood, mutilation, cannibalism, Santa Claus assaulting Jesus—lit by candles. They ran off screaming.

It turned out the mischievous neighbor was the collector’s nephew. The paintings had been passed along to his mother who, convinced that they were evil, banished them to the attic. She got rid of them, eventually, but claims not to remember the particulars. Their fate remains unclear.

— Anna Della Subin

Read A Very Still Life: Jack Kevorkian and the Muse of Genocide, by Anna Della Subin published in Bidoun, Issue 27 Diaspora on Bidoun.org.