Bent Is Best

A conversation with Sukhdev Sandhu

Sukhdev Sandhu is a British professor of English at New York University and a Contributing Editor at Bidoun. Since 2007, under the umbrella of a semi-secret society known as the Colloquium for Unpopular Culture, he has hosted hundreds of events, predominantly screenings, with an emphasis on the “banned, censored, and forgotten.” The Colloquium is luxurious in spirit: admission is free, there’s usually booze, scholasticism is discouraged, and the slightly shambolic atmosphere of repurposed classrooms and dimly-lit discourse is oddly, almost absurdly, welcoming.

The Colloquium is, by my lights, one of the main reasons to be in New York. Many a time, I’ve set out for an event on the strength of a film’s impossibly weird name or one of Sukhdev’s perversely enticing epithets (“seceding, barely there, out-where…”) and gone home marveling at my good fortune. (A case in point: The Cheviot, The Stag, and the Black, Black Oil.) The Colloquium is also one of the best ways to slip out of New York for an hour or two: a portal to startlingly intimate encounters with faraway places. In the last month alone, the Colloquium has assembled for:

a rare screening of Zinda Laash aka The Living Corpse, the primal scene of Pakistani horror cinema;

a womb-dark listening party for an LP whose German title translates to “Conversations with Larvae and Fossil Remains”;

the American premiere, 65 years after the fact, of British critic Kenneth Tynan’s disappeared documentary on American non-conformists, We Dissent;

a boozy Scottish wake for Keith McIvor aka DJ Twitch (Optimo); and

a meditation on medieval Christian mysticism and liturgical straws.

Every so often, the Colloquium goes for broke. In 2011, Sukhdev flew k-punk blogger and Capitalist Realism author Mark Fisher to New York to deliver a pair of influential talks. (In 2017, the Colloquium marked Fisher’s death with a moving multimedia memorial service.) There have been whole weekends devoted to Glam Rock, to the cryptobibliographical publishing house Strange Attractor, to the films of theorist Laura Mulvey, and to the life and art of avant-garde composer Arthur Russell. (Russell’s parents attended.) But its most ambitious project to date is “After the Watershed: Late-Nite TV From Britain,” organized with writer-curators Matthew Harle and Colm McAuliffe.

A monthlong program of screenings, talks, and hangouts, “After the Watershed” provided revelatory glimpses of subcultures, public intellection, class struggle, ripe humor, and off-piste drama, “broadcast” each day to a single cathode-ray color TV in the magnificently appointed premises of Various Artists, the alluring year-old gallery on New York’s Lower East Side.

In our open-ended conversation, Sukhdev discussed the Colloquium’s origin story, the dreamworld of fanzines, “fissile abstraction,” and the glamor of atypicality.

Michael C. Vazquez: I was going to ask you to narrate your backstory with Bidoun for the benefit of our newsletter readers, only to realize that we had already asked you to do just that some years ago:

Bidoun was farouche, knowing, a bit of a flirt. All good magazines should be. They exude strange aromas. They may want you to like them, but they should never say. A great magazine shouldn’t care if you like them or not.

Which was itself a bit flirty? In any case, I realized that I don’t really know how the Colloquium came about…

Sukhdev Sandhu: What happened is that I was back in New York after spending a lot of time in London working on what would become my book Night Haunts, and the English department was encouraging all sorts of working groups and collaborations at the time. I went to a few meetings, but it quickly became clear that everything I was interested in was of absolutely no interest to my colleagues—and that I was not all that interested in modernism, at least the way it existed in the academy. I didn’t pedestalize literature. I mean, I like literature, but there’s other things. And then one day I was talking with a very peppy former student of mine, James Brooke-Smith, and we were discussing what we were bored by. [Laughs] And the takeaway was that we both wanted more… primary encounters.

MV: Yes.

SS: And I was still reviewing films for the Telegraph at the time, with all the access that implies. I remember flying back to New York with a suitcase full of all kinds of incredibly rare materials and wanting to find a way to put them to use. And I think there was a kind of ecological thing, too. NYU has a lot of real estate, you know. We gobble up so much land, and it’s empty half the time. So it was important from the beginning that the Colloquium be open to the public, to make that space available to people outside the university. Which was not always easy, even then, and has gotten increasingly difficult, with all the politics of policing now.

MV: So you settled on close encounters with film.

SS: We did a series, which was called ‘Unseen Albion,’ which was films that were out of circulation. And I think the very first thing we screened was John Boorman’s Leo the Last (1970), this incredible satire about… failed gentrification? In which the deposed heir of some European royal family moves to Notting Hill and falls in with his Caribbean immigrant neighbors. The Colloquium’s publishing wing, Text und Töne, actually published a book about Leo the Last by Edward Platt last year.

The series also included Godard’s British Sounds (1969), The Fall (1969) by Peter Whitehead, and Punishment Park (1971) by Peter Watkins. Who just died last week, at the age of 90!

MV: That’s a lot of bangers. (In the American sense.) What about the name? Did you intend a particular provocation by standing with the unpopular?

SS: Well, numbers are rubbish, aren’t they? Universities are always going on about scaling up, accelerators, their own version of the “like and subscribe” button. I’ve no illusions that there’s a ginormous audience for what the Colloquium puts on, but then, as Andy Weatherall used to say, “Music: it’s not for everyone.”

MV: It is funny how all the talk of scaling up ends up making the world seem smaller.

SS: The world should be getting bigger! But if you’re in the academy, it so often just sort of feels pinched and squeezed. So I think I settled on the name as a way to maybe flush out a certain kind of person—you know, the kind of poltroon who might be drawn for some reason to the idea of unpopularity.

MV: Poltroons like us.

SS: I mean, you could see it as a bit abject or frivolous—I’m not going to pretend it has any great metaphysical depth. But there’s a Rebecca Solnit line that I quite like, from Hope in the Dark: “What is the purpose of resisting corporate globalization if not to protect the obscure, the ineffable, the unmarketable, the unmanageable, the local, the poetic, and the eccentric? So they need to be practiced, celebrated, and studied too, right now.”

MV: I mean, there are worse mission statements!

SS: Yeah. I remember an event, I think you were there, where somebody was showing a film of Viennese Actionists. We had people from the Whitney Independent Study Program, and their response seemed so cynical to me—basically, “Oh, it’s so easy to be doing that,” as if it were some kind of careerist master plan on the part of these young, sometimes morally defective, definitely over-passionate… whatever those guys were. And I thought, Wow, your education is doing active harm to you.

MV: Right. You are neither capable of being scandalized nor delighted by extremity.

SS: Or by anything. Neither scandalized nor delighted, because you run a risk by expressing an emotion, right? I don’t know. It’s always been about emotion for me, I think. Ideas and emotion. A couple of days ago, I was going through some old papers and I found some lectures that I wrote in my first job. And I thought to myself, I’ve been doing the same thing all my bloody life. Reading out thwarted love letters and raining down curses on a world of uber-scholasticism… But it did strike me, as I was tidying up those papers, that when I was about 15, all I ever wanted was a photocopying machine. I remember finding an ad for one in a local newspaper for 10 pounds. I was so excited! It was still a lot, but I persuaded my parents to give me the money. I don’t know where we would have put it? But then I rang the number and it turned out it was a misprint, and it was 1000 pounds.

MV: Of course.

SS: But my purpose was, obviously, to publish fanzines.

MV: [Laughs] Of course!

SS: I never liked the kind of reasonable fanzines that mimicked the style and the rhythms of the official press, whatever that is. I don’t want them to be inclusive, whatever that means. I like it when it’s just a mad, ranting person, who may be on a street corner or climbing atop a tower block roof with pirate radio equipment. When what it’s saying is: Here is a thing I’m really, really into, I think it’s great—don’t you?

MV: So should the Colloquium be understood as a sort of fanzine come to life?

SS: [Laughs] Well, I remember, around the time you introduced me to Shumon Basar, he was doing something with the idea of staging some sort of confluence of a magazine and live bodies in a room.

MV: Right. FORMAT, the living magazine.

SS: Yeah. I do think that’s interesting. I did an event for this really great jazz musician, Lol Coxhill, who died in 2012, and so much went into that. Most of the people who knew him are in their late seventies or older. And I was so nervous, terrified! His widow got in touch. I thought, you know, I just like his music. I wasn’t a friend. I didn’t know him. This is not my right to do this. But it was kind of wonderful. Maybe a bit like editing a magazine—you’re getting people to record things, getting people to find films that are not in public circulation, stitching together all these elements. Like laying out pages? Except the result only lasts, only really exists, for… 90 minutes? Two hours? For one afternoon.

MV: So wait, did you have a fanzine?

SS: Yeah, yeah. Well, just two. The first one was called Eheu! Caudex!

MV: Is that Romanian?

SS: Latin. It means “Alas! Blockhead!” And then the second one was called Ecce Caecilius, which basically means, “Behold Caecilius.”

MV: Was your fanzine about Ancient Rome?

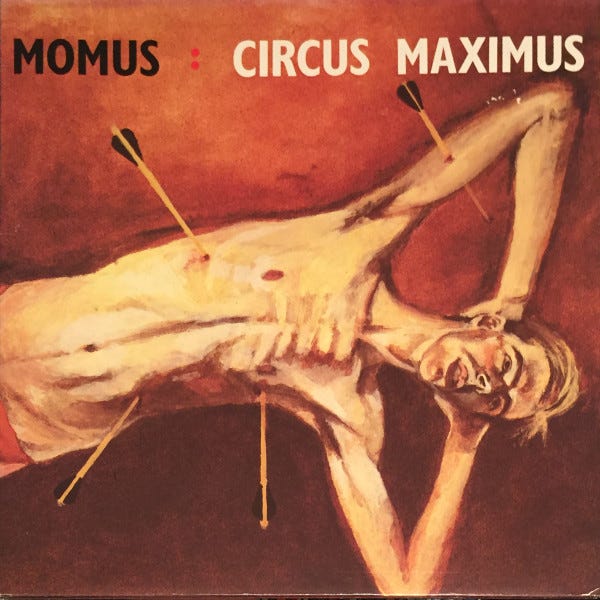

SS: No, no. I mean, it was mostly about music. Interviews. I talked to Momus—

MV: You interviewed Momus in high school?

SS: Yeah! Well, you know, he likes to talk, so I think he decided he preferred to talk himself. [Laughs] I discovered the tape recently and he’s remarkably precocious and up himself in the best way—waxing lyrical about repressed sexuality, about other people’s opinions of his looks, the problem with English culture. It was good!

And he’d been on this compilation of él records, and I love love love love loved él records. I interviewed one of their main songwriters, a guy called Philippe Auclair, also known as Louis Philippe, who’d been trained as a philosopher and later become a chef in Belgium and then released records under various pseudonyms. And who just looked dashing. I found some of his letters to me recently—oh! his lovely script! And I think they were on some kind of vellum paper which I’d never seen at that time. [Sighs] But él gets written out of a lot of pop music history. They were often described as this very playful, sort of whimsical, entity. Their first single was Shock Headed Peters, “I, Bloodbrother Be.” Which is the most cavalier, the most Soviet, tyrannical paean to violent gay sex that you can imagine. It’s really good!

MV: Did you have friends who were making fanzines at that time? Was there any sort of scene or…

SS: No. I didn’t know anybody. But I really liked one called Trout Fishing in Leytonstone that had stuff about the Situationists. And another, which only ever had one issue, called It All Sounded the Same, which was incredibly twee. I later discovered it was the work of Rob Young, who went on to write about much more punitive, attritional, conventionally complex music as editor at The Wire.

MV: I like The Wire as much as the next reasonable person, but it can be a bit grey.

SS: Sometimes. But It All Sounded the Same was like a riot of color! A lot of those zines, they weren’t the kind of… ransom note aesthetic of the industrial 80s. [Laughter] They were more… emotional pencil case. Sad rainbows of polychromatic glee. You get a sense that the music is just a crutch for them in all their spasticated adolescent yearnings as they try to imagine themselves out of their small town or little suburb or drab college room. Trying to will something into being.

MV: Is it possible that there is a quintessential Colloquium event?

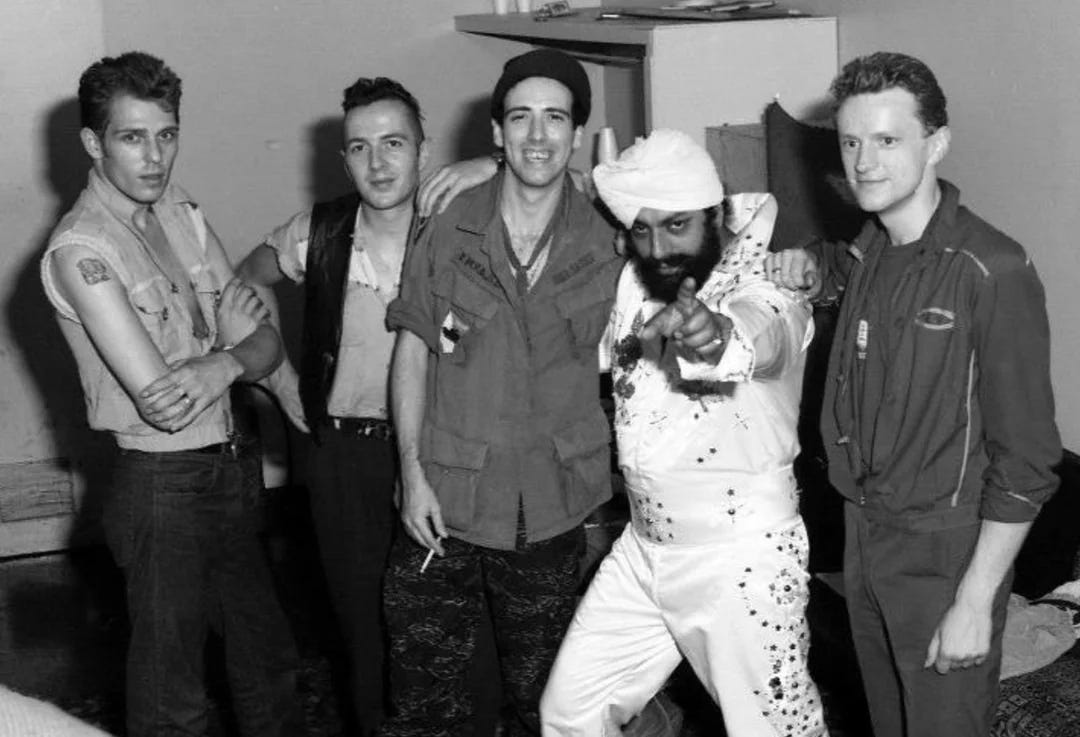

SS: Maybe the evening we did on Peter Singh, “The Rocking Sikh”—Britain’s leading Punjabi Elvis impersonator? [Laughter] Which we did with his friend Kosmo Vinyl, this brilliant guy, an artist who once upon a time helped manage The Clash. We showed this film, which is kind of lost in time—I think it was only shown regionally—about what it meant for him to see Jailhouse Rock as a kid and devote much of his life to becoming the Punjabi Elvis and the impact of all this on his slightly embarrassed daughter and wife. I’d got some people in Wales to do a bit of pre-record, and Kosmo brought out a painting that he’d done of Peter, and I brought in a 7-inch that he’d recorded, and we all sort of sat there together for an hour and a half. And I felt like, whatever my actual job is, nothing is ever going to give me more… pleasure or meaning or sense of purpose than being in a room of people, losing ourselves, thinking about Punjabi Welsh Elvis impersonators.

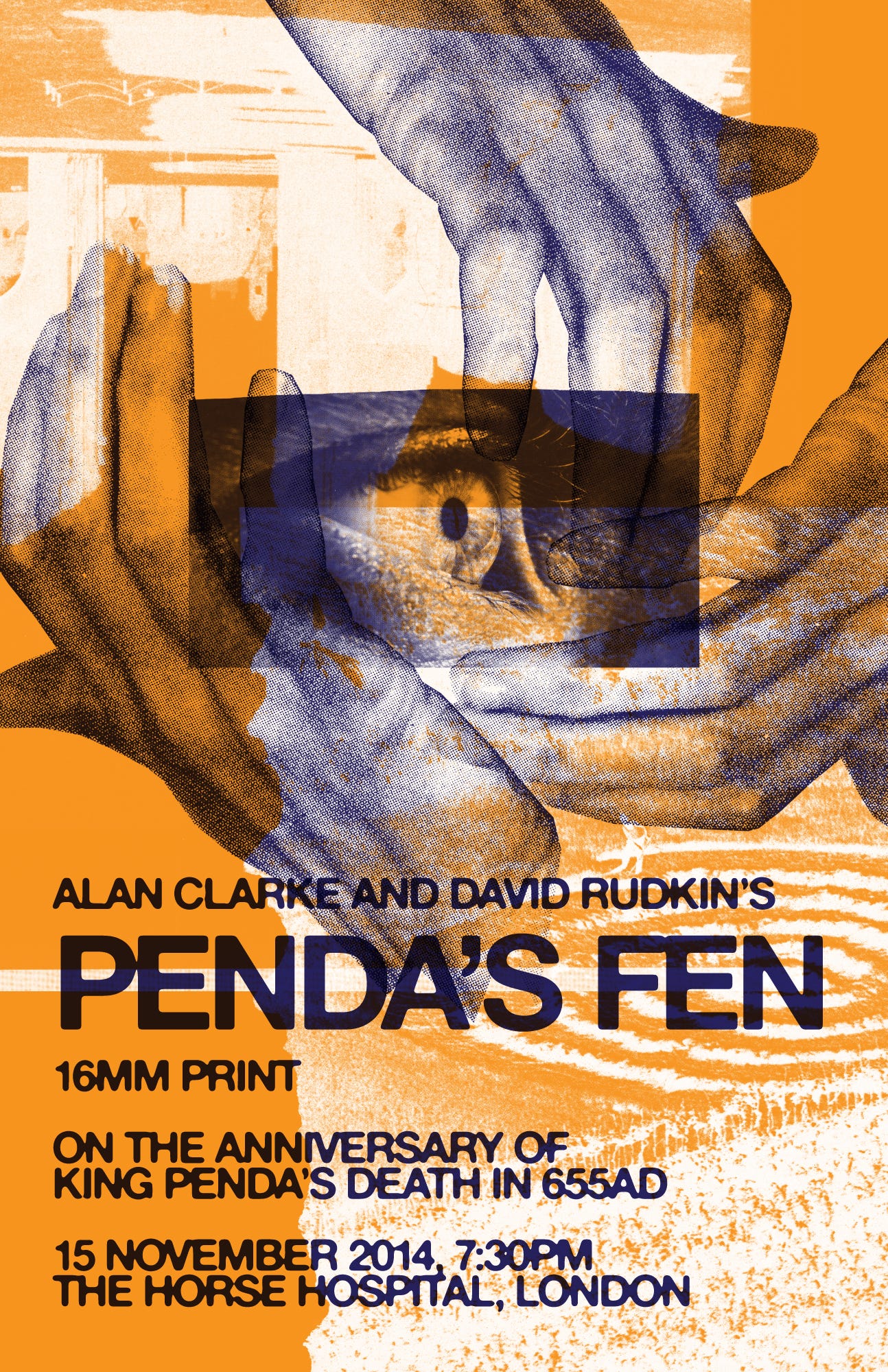

I mean, he’s probably nobody’s idea of Wales, of South Asians—of immigrants, even. Maybe people would think him wonky or absurd. But the Colloquium is happiest with the crooked. I love that Isaiah Berlin book, The Crooked Timber of Humanity. You know, bent is best. Or, as the title of our book on Penda’s Fen would have it: The edge is where the center is.

MV: It’s true! It makes me think of the Colloquium event celebrating Alex Keefe and his incredible essay in Bidoun’s Diaspora issue on Shridhar Bapat, an Indian expat in the early years of the New York video art scene.

SS: Gosh, yes. What on earth did we see that night? A goblin? A genie?

MV: I mean, we literally had a hologram of Shridhar. [Laughs] I forgot that part.

SS: It was so vivid. We were there to remember this pivotal and wholly forgotten figure, who spent his last years living in darkness beneath Manhattan, with all the chaos and collapse of that. But like, what was going on? We were all queuing up to meet him!

MV: I think I have a selfie with Shridhar, somewhere.

SS: It was like we’d held a séance, and he showed up!

MV: I guess you could say that one of the recurring themes of the Colloquium is the atypical Asian. The atypical yet exemplary Asian…

SS: [Laughs] That reminds me of another event a few years back, a triple bill of films about 2 Tone, the record label that launched the careers of The Specials, The Beat, and Madness. Which was based in Coventry, in the Midlands. So I wrote to Neil Kulkarni, this brilliant Asian writer, South Asian writer. He died just last year, horribly early. He used to write about hip-hop and metal for Melody Maker and Metal Hammer, really sweary, really vulgar, really funny. From Coventry. And I was like, Hey, I like your writing, would you consider doing some sort of introduction? And he said, Can I make a film? And I thought, Well, he’s going to sit in his bedroom and record a few things, sure, why not? And instead he went and bopped around town, shooting five different locations, and made this brilliant film about Coventry modernism. The city was one of the most bombed cities in the UK during World War II, so it became a bit of a tabula rasa for different waves of immigration. It’s sort of looked down on for having a very ugly accent. And this film was Neil saying, I fucking love this place, I love Cov, I’m never gonna leave. My politics, my music, my everything is here. He turned it around in about 24 hours! I was so blown away. I was so moved! The evening became a bit of a lock-in, with people dancing in the cinema aisles to “Do Nothing” and “Free Nelson Mandela.”

MV: Damn. I wish I’d been there.

SS: Yeah. But again, why was I so moved? I mean, it’s a big city, but in the scheme of things, you might think it’s not such a big deal. But the local and the small are really important to me. That sounds pompous, but it’s true. The small is really big! It’s like sitting in the front row of a cinema when that pixel in front of your face starts to look really weird. The screen is less about puncta of microscopic precision and more a kind of swarming, fissile abstraction. You start to lose yourself in it. The closer you go into anything, the more it sort of slips out of your ability to control it, to describe it. It becomes… well, I hope it becomes even more fascinating.

MV: Amen.

HOT TANGENTS

Guest curated by Sukhdev Sandhu

Music: A Selection of Music from Libyan Tapes

Habibi Funk is a brilliant Berlin-based record label that spotlights little-known or forgotten musical artists from the Arab world—particularly from the 1960s to the 1980s. Previous releases of note include a collection by Ibraham Hesnawi, The Father of Libyan Reggae; another by Sharhabil Ahmed, The King of Sudanese Jazz; and Oghneya, an astonishingly beautiful, Tropicalia-tinged LP from 1978 by the Lebanese band Ferkat Al Ard. A Selection of Music From Libyan Tapesshowcases tracks from the late 1980s to the early 2000s that are synthetic, spacey, and, in the case of Khaled Al Reigh’s “Zannik” (a cover of Pink Floyd’s “Another Brick in the Wall”), an authentic dance hall bubbler.

Film: Edward George, Black Atlas at the Warburg Institute, London

Eddie was a founding member of the Black Audio Film Collective. He was the Data Thief in the BAFC’s The Last Angel of History (1996), a foundational document for what came to be known as Afrofuturism. His ‘Strangeness of Dub’ radio series features two-hour programs in which black British history and cultural politics are dramatized through dialectical soundclashes between Jah Shaka and Dennis Bovell. Let loose among the collections at London’s augustly peculiar Warburg Institute, he has created Black Atlas, a looping essay film about art, blackness, and spectrality—a kindred spirit to John Berger’s Ways of Seeing and Laura Mulvey’s “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.”

Music: Arja Kastinen & Taito Hoffrén, Teppana Jänis

Death Is Not The End is a wonderful label whose ambit spans Iberian-Pakistani Sufi Flamenco, Jamaican Doo Wop, Brazilian country music, early 1930s Sacred Harp singers, Shidaiqu pop from late 1920s Shanghai, mushroom ceremonies of Mexico’s Mazatec Indians, Greek rebetiko, Japanese ryūkōka, pirate radio ads… Its founder, Luke Owen, who did a Colloquium event in 2023, says that what unites these disparate musics is “timeless emotion, fragility, nostalgia, a lot of despair, some humor here and there.” This recent release hearkens back to World War I, when Teppana Jänis, a blind kantele player, helped Finnish folk music researcher Armas Otto Väisänen record traditional shepherd melodies on wax cylinders. Wisps of those century-old recordings are commingled with modern-day renditions by researcher Arja Kastinen and singer–composer Taito Hoffrén; the results are heart-stopping, beyond words…