APAS

A Protest Against Spaghetti is live this week, an opportunity to feature shorter, timelier, more casual content: interviews, as-told-to’s, diaries, recommendations, pictures, moving pictures, mix tapes, listings of Bidounish happenings across the globe, & much else.

Artists Valentin Noujaïm, Meriem Bennani, and Orian “Yani” Barki have film debuts in New York City this week. Bennani and Barki’s first feature, a queer, animated coming-of-age story titled Bouchra, graces the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center from Saturday, September 27, through Monday the 29th. Earlier this week, Noujaïm’s trilogy of films set in the Parisian business district of La Défense screened at the Museum of Modern Art.

On Friday the 26th, Bidoun will be presenting Pacific Club (2022), the first film in Noujaïm’s trilogy, at 99 Canal. Set against the backdrop of racism, a heroin epidemic, and the emerging AIDS crisis, the short film evokes a nightclub that catered to a mostly young, mostly Arab clientele during the 1980s. The screening will be followed by a conversation with writers Perwana Nazif and Adam HajYehia and a launch party for Interzone, Noujaim’s first monograph, published by Kunsthalle Basel and Mousse.

For this inaugural edition of Bidoun’s newsletter, Barki and Bennani met up with Noujaim to talk about their latest work and mutual interest in speculative worldbuilding.

Valentin: You and I have many things in common, like how we like to mix the real and the unreal, documentary and animation. Why do you create this way? What do you want your worlds to do?

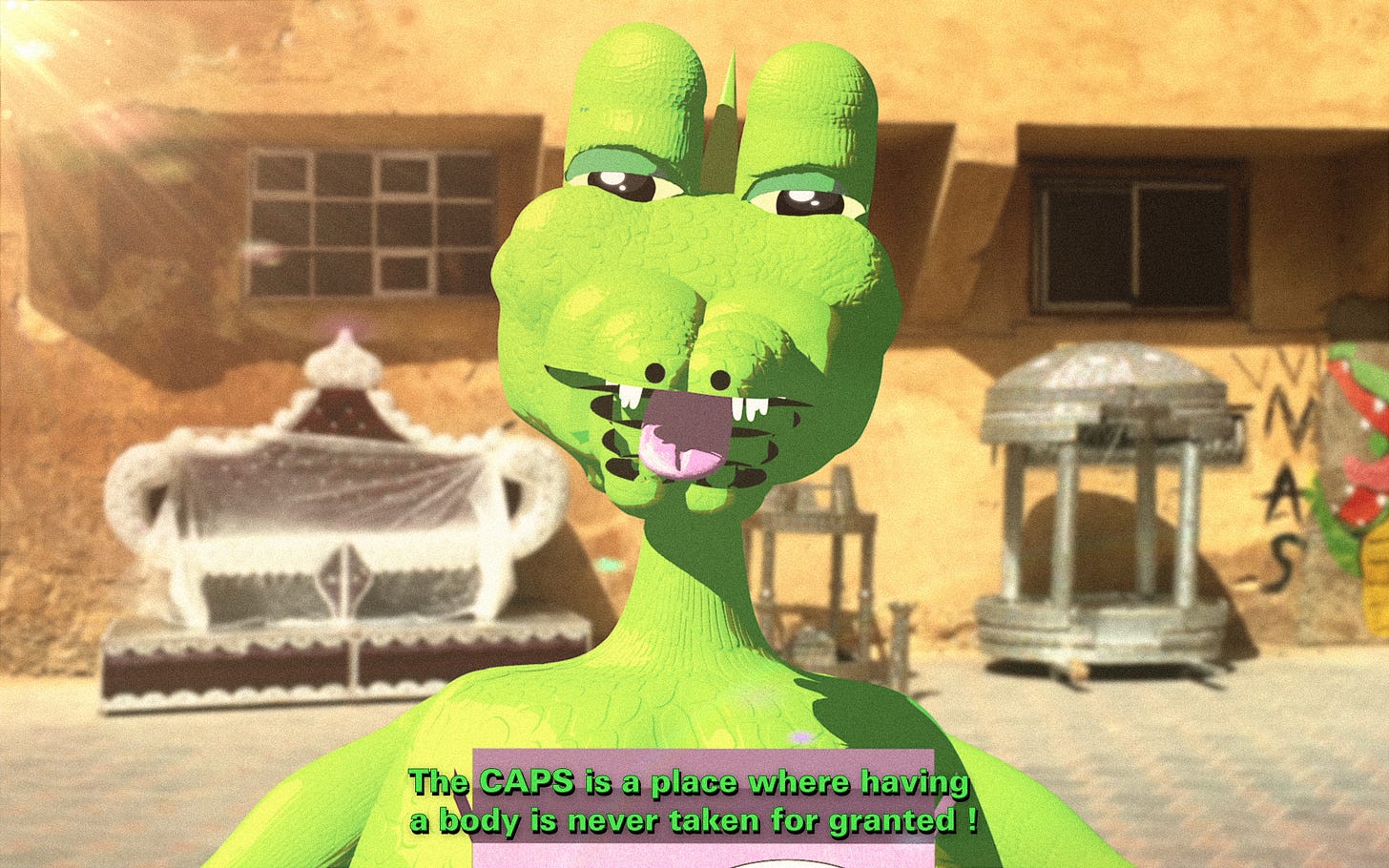

Meriem: Well, sometimes I establish a speculative space for the actors who are playing themselves in my films — for example, with Life on the Caps, I wanted them to believe they were in the future. As for the documentary aspect… I think it’s obvious that I’m not trying to pass it off as “real.” It may be strange, but I think of the staging of documentary footage as more like creating a narrative proxy—a way to put people in situations where they can express themselves while engaging in roleplay. It allows something else to come out in the work that’s not speculative, but very much about the present.

Valentin: That was absolutely the case in your Life on the Caps trilogy, which takes place on a fictional island in the middle of the Atlantic. The island is a futuristic detention camp for migrants. You don’t have to look at it very long to see that your image of the future looks very similar to… now.

Meriem: I think what the three of us have the most in common is that we work with reality. But what is your process like, Valentin? Do you shoot first and then construct the rest in post? Are your scenes fully scripted, or do you improvise with your performers, or…?

Valentin: It depends. It’s funny because I got my degree in screenwriting at La Fémis, in Paris, but I kind of hated it. [Laughs] I ended up wanting to escape writing—to do something that felt a bit more alive. Of course, I still write, but I leave room for other things to enter the script. For example, To Exist Under Permanent Suspicion (2024), the second film in the Defense Trilogy, developed out of my interactions with the lead actress, Kayije Kagame.

Meriem: She was amazing in Saint Omer (2022), the Alice Diop film.

Valentin: She was! In my film, she plays a businesswoman promoting a new skyscraper who slowly goes mad… I had just seen her perform a very long monologue from Jean Genet’s The Maids, so she was primed to inhabit a person who is entrapped by the system. I had a set, and I had some ideas, but Kayije brought a lot of her own gestures and ideas to the project.

On the other hand, Demons to Diamonds (2025), the third film in the trilogy, is very scripted, very heavy on dialogue and character. Oddly, it’s the film I made that feels closest to a cartoon, because the model for the city was very inspired by the look of Gotham in Batman, the animated series, which I loved when I was a kid. But even when I work with documentary footage, like in Pacific Club, where my main subject was free to say whatever he wanted—I remain in control of the narrative. So how “real” that film is is up for debate.

Meriem: I actually think there’s no such thing as pure documentary. You always have to tell people where to sit or stand, you’re deciding how you want to film them, you control the edit. Documentary is a construct — maybe especially with films that are trying to look the most like reality. I’m glad you mentioned cartoons! Yani and I were wondering if you’re a fan of anime, because the look of your films is so particular, so anime-like. We both thought about Ghost in the Shell, Perfect Blue…

Valentin: I am very influenced by anime, it’s true. But I’m also very influenced by theater — the way it’s always playing with reality, inside/outside. Audiences have to accept that there’s something behind the backdrop, behind the sets, you know? I see the same kind of theatricality in your work, too. I always have the strange feeling that there’s something or someone watching the characters, even watching us viewers, too.

Meriem: With Life on the CAPS, that feeling you describe of someone looking at you — I think it might just be me! [Laughs] I’m definitely always reminding viewers that I’m there through my little interventions — mostly animation — reminding them that this world is not real, that the story is constructed. Even when it’s my story.

Valentin: Bouchra really is your story, right? It’s very personal.

Meriem: Yeah. Initially, we wrote a script about a mother and a daughter and their complicated relationship. It was heavily inspired by my life, but I wasn’t ready to make the film autobiographical, at first.

Yani: We actually had a running joke at the studio: “This film is not about Meriem!” We wanted the story to seem very far from reality. We were scared, actually — fear shaped how we wrote it. But at some point, we got really stuck. And then came the phone calls between Meriem and her mom…

Meriem: I think there’s good fear and bad fear. Good fear is the kind that arises when you care about what you’re doing, so you feel nervous. But the fear that Yani mentions was a bad fear — it was our fear of falling into the classic “coming out” story trope. We were scared that it was going to be misunderstood. And I was scared because it’s my story and I didn’t want to pretend like I’m telling the story of every queer person, because I’m not. So we wrote a script that we were kind of happy with but maybe not excited about. We felt that it was missing something. That’s when I decided to ask my mom if I could record a conversation with her about my queerness.

Yani: When we listened to the recordings, we thought, Fuck, this is so much better than anything we’ll ever write. The dialogue was so specific — it had all this nuance. So then we went about creating a meta-narrative. We made Bouchra, the main character, a filmmaker who’s working on the script that we originally wrote. To help her finish her film, Bouchra calls her mom…

Valentin: I think you not only escaped all the traps of making a coming-of-age queer film, you managed to avoid exoticizing queer Arabness.

Meriem: Thank you! Can you speak about your relationship to Frenchness? I feel like you’re part of a group in France, let's say children of colonialism, who are increasingly making art about those legacies and realities. As a Moroccan with a French colonial education, I’m totally interested in this phenomenon.

Valentin: My first films were much more about Lebanon and Egypt, where my parents are from, but those places were a bit distant for me because I’m part of a diaspora. I realized that the reality I could talk about the most was France. I grew up in this country and feel very fearless about speaking to it. A portrait of La Défense, a business district in France, will inevitably be a portrait of those postcolonial legacies. To build it, they tore down a shanty town full of migrant workers who had been forcibly brought to France from the Arab world — Algeria and Morocco, mostly. And of course, the central figure in Pacific Club, Azedine Benabdelmounene, is of Arab origin. We know that France continues to have a complicated relationship to its Arab Others. This newfound visibility that you speak of, it’s a bit paradoxical. It exists, and yet it still takes years for us to get shows in major French museums… if it happens at all.

Meriem: For sure. [Laughter] Tell me, how are you feeling about screening these films at MoMA?

Valentin: I’m excited to be showing the three films as a trilogy, one after the other, and seeing how the responses in America might be different from what I’ve received in France. What about you? This is Bouchra’s first time in New York, yes?

Yani: It feels like pure fun to show it here. We’ve been working on it for so long — we’re ready for it to be out in the world.

Meriem: We want to be exorcised of it. [Laughs] I’m already dreaming about the next project.

Hot Tangents

Last week we published Bidoun’s most viral article in recent memory: House Arab, the story of a fact checker at one of America’s most prestigious magazines and his crisis of conscience in the aftermath of October 7th. Look out for a Q & A with its author, Ismail Ibrahim, in our next newsletter.

Bidoun contributor and friend Alaa Abd El Fattah is free. Alaa has spent much of the past fourteen years in prison or detention in Egypt. Read Lina Attalah’s recent piece on Alaa for Bidoun, & here’s a selection of his essays & interviews from our archive.

168 Hours of Resistance: a 24/7 live transmission of fragments and voices on the theme of resistance, running this week only, September 20-27. Organized by Ibrahem Hasan.

More from Meriem Bennani in Bidoun: a 2018 music mix (originally deejayed at MoMA PS1) and a conversation around Life on the CAPS with Fatima Al Qadiri.