2025: The Year in Bidounica

In which there are no bests, only favorites.

IN THE BIDOUNIVERSE, 2025 will be remembered as the year of Zohran Mamdani, whose victory united multiple ecologies—from community centers in Queens, to immigrants’ kitchens, to college campuses, and the city streets —into a viable municipal vision. If he is the apotheosis of the Bidouni—and he is—it’s because he wears his contradictions plainly: a socialist who knocks on front doors to fundraise, a friendly New Yorker who chats with strangers on the subway and smiles so much I have grown concerned about his jaw. He says nothing untoward, his politics are legible, his backstory exquisitely scrambled, and his left(ish) policies seem on their way to being semi-safely routed through the circuitry of governance.

The cynic in me, perhaps in every New Yorker, wonders if there’s something plastic about his promises, or if he’s perhaps too good to be true. Zohran may not be able to stop the firing squads, but I for one trust that he’ll at least make sure we’ve all received our fair share of blindfolds and cigarettes.

Zohran can’t abolish the system, but he can dissent inside of it—a fact that has this city feeling, at least temporarily, relieved, even hopeful.

For more on what we at Bidoun loved in 2025, see our contributing editors’ offerings below—and do subscribe to this Substack if you haven’t yet!

And coming in 2026, a conversation with filmmaker Mira Nair, now known as the Mayor’s Mom, as she looks at the year ahead with us.

—Zain Khalid, Contributing Editor

Negar Azimi

Until his death last spring, Walid Daqqa (1961–2024) was the longest serving Palestinian political prisoner in Israel. Locked up for his role in the kidnapping of an Israeli soldier—a charge he denied—Daqqa turned his nearly four decades in prison into a sprawling intellectual project, pursuing two degrees and writing multiple books, mostly about the carceral system that had entrapped him. Writer Kaleem Hawa evokes Daqqa’s life and remarkable work, and the efforts to extinguish them, in “Like a Bag Trying to Empty,” a moving portrait published in Parapraxis magazine later made into a chapbook by the excellent, Brooklyn-based literary non-profit, Wendy’s Subway. Daqqa’s story is an epic, and Hawa traces it from his early life through his intellectual formation to his wedding to journalist Sana Salameh in 1999. When the Israeli authorities denied the couple’s desire to have a child, Daqqa’s sperm was smuggled out to produce a daughter, who would later refer to the prison that held her father as “a place without a door.” At a time when the systematic erasure of Palestinian life is upon us, Hawa’s ode to Daqqa, who remains in postmortem detention, is a vital protest against forgetting.

Sophia Al-Maria

My favorite thing that happened in 2025 was seeing Kneecap in Belfast in August. I chose a gravel pit over a beach for my birthday, which felt exactly right. It was the hip hop trio’s prodigal return after a year marked by British state scrutiny, legal battles, and the ongoing terrorism charges facing founding member Mo Chara, and being there felt like a small act of alignment as well as an opportunity to learn more about Northern Ireland, the Troubles, and the long history of criminalizing language and resistance. I wore a white, one-of-a-kind, charity shop resurrection (cost: £9.99) adorned with mismatched ribbons and pins and bearing a hand-painted lyric from their song, “Guilty Conscience:” I MEDITATE & HAVE PLENTY OF WANKS. (To go in deliberately virginal drag was a rare choice for me.) My look nodded to a Vivienne Westwood bodice, and was worn over a football kit I made from Sudan and Palestine jerseys as a love letter to linguistic insurrection and DIY glam. A curator later noticed my outfit and included it in the installation “Club to Couture” at the Barbican in November, where it appeared with a Leila Khalid pin—small representation, big satisfaction. Among Kneecap’s fans there was no merch save for a single poster, the proceeds of which went to medical aid for Palestine, which I respected deeply. I love Kneecap because the world needs more holy fools, like artists who hold joy and rage at once and refuse to dilute their politics no matter the cost. In the gravel pit of Boucher Fields, I was covered in mud and other people’s beer. I felt filthy but I also felt free—and was surprised to see so much pride in Palestinian solidarity in a heaving mass of folks who, after near-twenty years living in the grey unpleasant land of England, I would have reckoned and judged to be the type who’d be at a National Front rally. It was a real lesson to me, plus I got a bonus treat: an old flame laid a well-timed kiss on me high above the crowd on a Ferris wheel at exactly the moment the band ended and the field erupted in applause. May we all have more love and less shame, more revolutionary spirit and less power-pleasing, and more readiness to fight until we are all free. Palestine remains the key.

Zain Khalid

The Calf (Deep Vellum) by Norwegian writer Leif Høghaug has arrived in English much in the same way that its narrator, a garden gnome from Appalachia, wanders down a Norwegian mountain after decades of rural life in his adopted homeland: speaking three dialects yet getting none of them quite right. Translator David M. Smith—God bless him—has done more than merely render Høghaug’s words comprehensible; he’s staged a jailbreak, language coming out kicking, bleating, chewing through the fence. English, being so expansively simple, seems a last and perfect resort. Misfired idioms, wayward syntax. The Calf is what happens when Robert Frost’s tweaker cousins translate Marx while high on pine sap.

As for plot . . . there are cowboys and aliens. Christ comes again (along with a social worker). Pencils are sharpened. The gnome makes coffee. He’s solving a mystery. The calf is dead. Don’t get the gist? I don’t either. A screaming comes across the sky. This is why I dig it and why I can’t help but dig it. For every “social-climbing critique” novel, every “jet-setter ennui” novel, every “artistic-friendships-aren’t-what-they’re-cracked-up-to-be” novel, there should be one about a garden gnome with a bucket on his head talking in a language that only he understands. It’s the rare book that reminds you English is not a home but a temporary shelter, for writer and translator both, and can be built and rebuilt, in this case from warped driftwood that the North Sea has coughed up.

Yasmine Seale

This year I saw three of my musical heroes perform in New York: Jordi Savall, the Catalan viol player and scholar, who traces the entangled sounds of the Mediterranean; Simon Shaheen, a Palestinian virtuoso of both oud and violin, who embodies a lifetime of listening across worlds; and Cécile McLorin Salvant, a French-American vocalist of dazzling range, who treats the history of song as a living archive. Here she is at the Met Cloisters performing a lyric by the twelfth-century female troubadour, Almucs de Castelnau, first in Occitan, then in Haitian Creole.

Sukhdev Sandhu

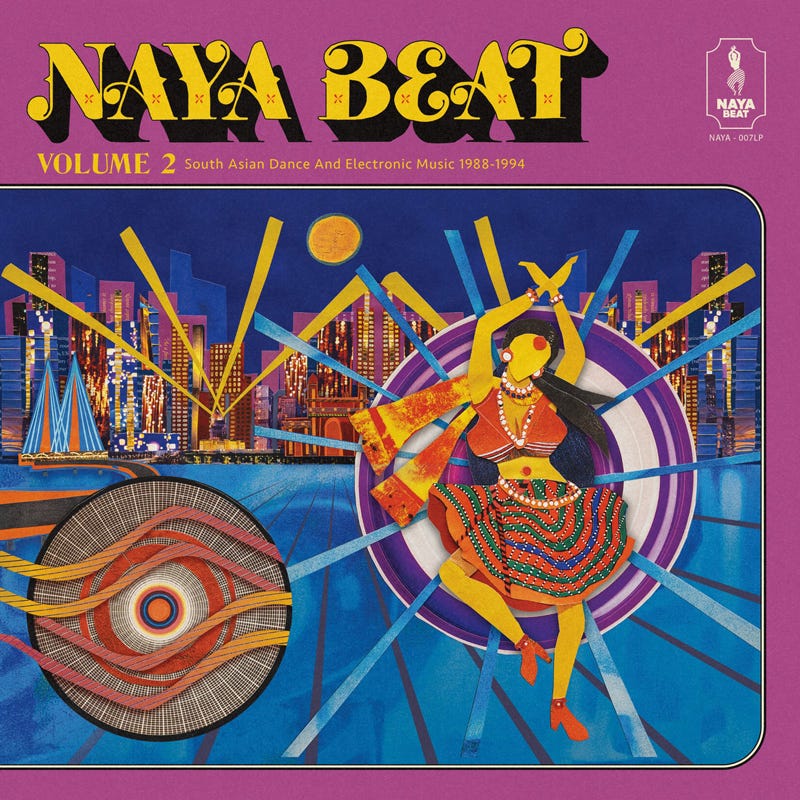

When I was a boy, I used to scream and shout—to reggae and Rebetika, jazz and jangly pop. Some of those musics, for a long time neglected or even derided by airtime controllers, have since spawned publishing industries. Music by brown-faced Brits was always patronized, a cut below. No surprise then that it’s taken a West Coast label, Naya Beat, to explore some of the piquant Punjabi tunes that came out of the UK from the late 1970s to the early 1990s. Teri Liye by Pinky Ann Rihal; Punjabi Disco by Mohinder Kaur Bhamra; almost anything by Bappi Lahiri. There’s bits of post-punk wobble here, avant-la-808 techno, Italo idiosyncrasies. Left field, ahoy!

Broadcast since 2006, Great Lives is a BBC Radio 4 series in which guests get the chance to salute someone important to them. This autumn, when stand-up comedian Stewart Lee came on to celebrate improvising guitarist Derek Bailey, presenter Matthew Parris expressed his dismay, likening Bailey’s style to that of a chimpanzee. What resulted was the best bit of radio in a long time. “Matthew, that’s such an idiotic thing to say. A chimpanzee doesn’t even have the fingernails to make that sound,” retorted an exasperated Lee. “You’re on the BBC, right? You’ve got to meet the challenge of a culture that is failing artists, and failing the public. . . .Also it’s such a cliched thing to say a chimpanzee. At least say an octopus. Or a wasp, for God’s sake.”

Lucky are those scribblesmiths in the United States and beyond who, these last ten years, found a berth at 4Columns. Founded by Margaret Sundell in 2016, it gave the much-concussed class of art writers a lushly designed platform to think aloud about work that puzzled, irritated, spirited them. What made it such a pleasure to contribute to were the editors: Sundell, Melissa Anderson, and Ania Szremski, who also happens to be a former curator at Cairo’s Townhouse Gallery. The speed and elegance with which they alighted on my many grammatical infelicities, tarted up my bromides, proposed defter syntax—they were, are, all great writers themselves. Tireless, too. Ania, scenting a potentially slack metaphor, once spent hours researching the sounds that different types of dinosaurs made. 4Columns will shut up shop this coming summer. Alas, and thank you, Margaret, Melissa, and Ania.

Jennifer Krasinski

EXPtv.org isn’t new, but the incredible volume of rare media streaming nonstop on this channel—available on their website and on Twitch—makes you feel as though you’ll never step in the same river twice. Brought to you by archivists and editors Tom Fitzgerald, Marcus Herring, and Taylor Rowley, and their full-to-bursting hard drives, EXPtv offers up original programming with titles like “Plants are People Too,” “Kung Fu Wizards,” “Everybody is a Star,” and “Night Comfort,” deftly cut together from found films, videos, television shows, commercials, and all kinds of mesmerizing ephemera. No outlet for mere nostalgia, the channel in fact offers subterranean lessons in media history. Take “Nothing But Star Wars,” an hour-long collection of clips from rip-offs, run-offs, and remakes of Lucas’s landmark movie—including a genuinely baffling porno—that may just be the greatest essay on the dawn of global blockbuster culture. In the background as I wrote this, EXPtv featured a snippet from a Christian call-in talk show in which the host plays Led Zeppelin’s “Stairway to Heaven” backward to prove that the words “my sweet Satan” are secretly embedded in the lyrics, followed by a scene from Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood in which Daniel Striped Tiger asks what “assassination” means. On EXPtv, as in life, there is no rewind button, no turning back the clock, only the recognitions and revelations that come with hindsight.

Sohrab Mohebbi

In a world littered with biennales and blockbuster shows making lofty claims, MONUMENTS is a true historical feat. Co-presented by the Brick and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles through May 3, 2026, this exhibition brings together a number of decommissioned American Civil War monuments, mostly Confederate, offering up a discursive engine that furthers debates around the role of art in the making of history. These objects are extraordinary examples of public art—civic, aesthetic interventions in public space, the most captivating of which bear the marks of social upheaval, predominantly in the form of graffiti. Others, seemingly untouched, are no less transformed by being removed from their pedestals through the sustained work of activists.

The monuments are installed alongside contemporary interventions that, for the most part, feel secondary to the exhibition’s otherwise groundbreaking proposition. The exception is Kara Walker’s Unmanned Drone, her forensic dissection of a monument to Confederate General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, who she’s reassembled into a minotaur. This piece ranks up there with A Subtlety, her 2014 larger-than-life sugar sculpture of a Black female figure in the form of a Sphynx, as one of the most significant works of American art so far this century.

Yasmine El Rashidi

Lara Baladi’s Cosmovision at Tintera Gallery, on view through January 11, marks a rare presentation by the artist in Cairo after over a decade away. Structured as a concise, almost-mini-retrospective, the show compresses the long arc of her practice into a tightly curated sequence of works that defy the usual formalities of installation: some images are framed while others are simply pasted atop brightly colored walls or wallpaper; one of the rooms is designed to mimic a space from her past. The exhibition recalls Baladi’s emergence in the 1990s with large-scale photographic collages and kaleidoscopic constructions that challenged linear narratives and fixed points of view. Yet here she is repositioned not as a historical footnote within the now-contested history of Cairo’s downtown art scene, but as a figure pivotal to its early formation, one whose sustained interrogation of image, power, and memory remains unresolved, ongoing, and necessary.

Elizabeth Wiet

As a high school journalist, I had two main beats: Morrissey concert reviews and screeds against George W. Bush. Reading one of my old clips, a friend quipped, “This article is funny because you’re trying to sound like a hardened DC political commentator, but you’re actually a teen girl in rural Illinois.” That same self-aggrandizing sincerity permeates Jesse Moss and Amanda McBaine’s documentary Teenage Wasteland, which revisits a story of corruption in the Hudson Valley first reported by a group of Middletown High School students in the early 1990s. The students are Gen X archetypes: weekend goths, stoners, and would-be burnouts who find renewed academic energy in their delightfully named “Electronic English” class, where they learn the ropes of media production from teacher Fred Isseks, who is as ideologically radical as he is Hollywood handsome. After the students discover that corporations are conspiring with the mafia to illegally dump toxic waste in a nearby landfill, Isseks encourages them to document the story, despite resistance from local officials intent on covering it up. Having long since traded my reporter’s notebook for a classroom lectern of my own, I could not help but be moved by Isseks’s stalwart insistence that his students dare to dream. Think Dead Poets Society meets All the President’s Men, preserved on grainy VHS.